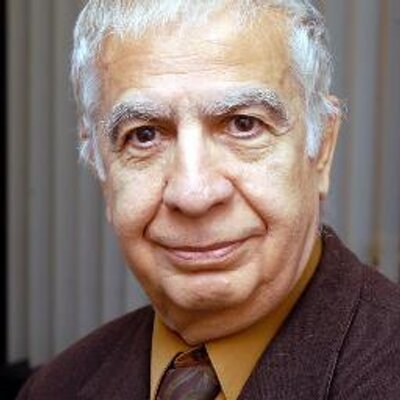

THE "OREINTALIST" BLOWS 100 CANDLES Mention the word "Orientalist" almost anywhere and you are likely to hear the name of Bernard Lewis as the best embodiment of that hotly debated distinction. Designating Professor Lewis who has just marked the first centenary of his life as an "Orientalist" is not surprising since the area of his scholarship, the Greater Middle East, has been equated with the concept of "The Orient" since the 18th century. There is also the fact that more than a dozen books have been written attacking or praising the Jewish-English scholar as a leading member of an academic fraternity in the West. Although I regard the title "Orientalist" as a badge of honor for the hundreds of men and women who, over more than two centuries, helped the people of the Middle East, including my own in Iran, learn aspects of their history and culture that they had had forgotten or ignored, I think applying the title to Bernard Lewis would be reductive. The traditional Orientalist like Herzfeld, Ivanov and Petroshevsky regarded his "Orient" as the backdrop of atrophied civilizations that had reached the limits of their development and were now on autopilot, so to speak. Some like Chateaubriand or Pierre Loti for that matter in search of exoticism to inject some color, or perhaps even life, to what they regarded as the frozen reality of Western lives. Others like Champollion or Edward Brown went to decipher ancient alphabets or repertory dead literatures. Still others like henry Corbin and Louis Massignon looked for hidden layers of old spirituality while ignoring the here-and-now of their "Orient". For still others, say Max Mallowan or Andre Goddard the "Orient" consisted of archaeological digs in the Levant or Persia with the promise of furnishing relics for display in Western museums. At the lower end of the "Orientalist" hierarchy we also had the so-called "les turcs de profession" (professional Turks) whose business was to flatter the "Orientals" for profit or political seduction. In that category we had the Nazi scholar, a contradiction in term, Sigird Hunke who wrote a 700-page book to "prove" that Europe owed everything worthwhile to the "Islamic orient." Some like Vincent Monteil or Roger Garaudy insisted that only mass conversion to Islam could save Christendom from decline and doom. At the other end of the spectrum, there were those who regarded the Islamic "Orient" as modern civilization’s nemesis to be fought and destroyed. (Stalin created a Soviet League of Atheists for that very purpose.) In fact, he is hard to categorize if only because he was active on several different tableaux. To start with he was certainly a historian of great distinction with a record of original research especially into the immense political and legal heritage of the Ottoman Empire. At the same time, he was a keen student of Islamic schisms, especially aspects of the "ghulat" or "exaggerated" theology of Ismaili faith and its many offshoots. Having learned Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Hebrew he had direct access to the written heritage of his" Orient", something many "Orientalists" could only envy. More importantly, perhaps, Lewis quickly realized that the Middle East was not a mere graveyard of civilizations and faiths but the home of living and dynamic societies that could develop and grow in different, at times even opposite, directions. Thus, while, as historian, he was focused on the "there-and-then" of the region, Lewis was fully aware of and interested in the here-and-now of Middle Eastern societies. His Zionism, acquired before he became a scholar, reinforced his interest in the here-and-now of a region that was to morph into the center of so many international conflicts after the Second World War especially with the re-emergence of an independent Israel. Scholar, historian, linguist and researcher in theology, Lewis also became what the French call a "public intellectual", a role he emphasized in the later decades of his life especially after the 9/11 attacks on the United States, his adopted home away from his beloved England, and the subsequent "liberation" of Afghanistan and Iraq in the early years of the new century. In both his work on history and his translations from Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew and Persian literature Professor Lewis has adhered to the highest standards of scholarship that made English academia a role model for the world for more than two centuries. I first met Lewis in the early 1970s during one of his visits to Tehran, the Iranian capital, when he was granted a long audience with the Shah. At dinner party, given by Fereidun, brother of the then Prime Minister Amir-Abbas Hoveyda, Lewis talked of his concerns to a group of high officials and intellectuals. I liked his critical remarks because they went against the protocol under which foreign dignitaries visiting Tehran met the Shah, praised his wisdom to the sky, visited Shiraz and Isfahan, received their carpet and caviar gifts and flew back home contended. Lewis criticized us because he respected and, perhaps, even loved us a little bit. Lewis’s honesty and rejection of all sycophancy earned him many enemies especially among Islamic intellectuals of the Left who cling to their Blame-America-First shibboleth to avoid any criticism of their own societies. However, there were, and are, also Muslim intellectuals and politicians who appreciate the centenarian professor’s frankness even when in mordant mode. I remember a dinner party in the early 1980s at the house of Turgot Ozal, later President of Turkey, when Professor Lewis, always an ardent supporter of the Kemalist republic, told his audience of mostly Turkish politicians and intellectuals that secularism did not mean the crushing or religion by the state. Ozal, at least, understood the significance of the remark and, I believe, kept it in mind when he achieved high power. Professor Lewis also sued the same frankness with the Israeli leaders when he advised them not to try and ask too much from the Egyptian President Anwar Sadat once he had made the choice of peace. At the same time, through contacts in Sadat’s entourage, he advised the Egyptians to moderate their rhetoric. The first was when, in the 1980s, I argued that Muslim communities in the West could become centers of enlightenment projecting "light" back to Muslim countries. He disagreed, dismissing my idea as naïve and Panglossian. Almost three decades later and after so many things that have happened in Europe and North America, I must admit that he was right ad I was wrong. Today, more darkness is exported from the Muslim communities in the West to the Middle East than the other way round. Our second disagreement concerned Professor Lewis’ celebrated "Clash of Civilizations" essay published by the Atlantic Monthly, later inspiring Samuel Huntington’s bets-seller with the same title. My argument was that Islam was not a civilization but a religion that had contributed to many different civilizations and that the problem today was the transformation of Islam into a radical political ideology that regarded modern civilization as enemy. In fact my argument was partly inspired by some of Lewis’ own work, notably his work on the historic encounter between Islam and the West and, more recently, the failure of Westernization attempts in several Muslim countries, exposed in masterly fashion in his "What Went Wrong: The Clash Between Islam and Modernity". Thus, while Islam is certainly incompatible with democracy, democracy isn’t incompatible with Islam. Bernard Lewis decided to study the Middle East in the 1930s when almost no one was interested in the region. While historic events have provided the context, Lewis’ magisterial work has greatly contributed to keeping the turbulent region at the center of academic and political interest for the past six decades. END |

التعليقات