&

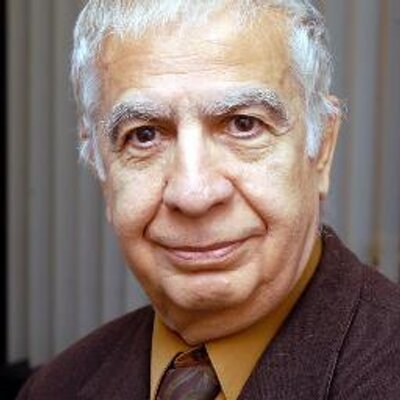

IRAN: A PLAN B Paper presented by Amir Taheri on 27 November 2018 at special seminar at Westminster University in London, United Kingdom. The seminar was attended by Iranian political activists and foreign diplomats, academics and media people.& IRAN: A PLAN B EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Those having problems with the Islamic Republic have contemplated, planned and, in some cases, even tried quite a few Plan A options to deal with the Islamic Republic. These range from efforts to persuade the current leadership in Tehran to change aspects of its behavior to economic warfare, “crippling” sanctions, and, on occasions, even military action. All those plans failed to produce the desired result because they were based on the assumption that the Islamic Republic is a classical nation-state and likely to respond as such. However, in its revolutionary emanation, Iran has experienced what could only be called an historic schizophrenia in which its identity as a revolutionary cause is in conflict with that of its identity as a nation-state. The net result is that it can neither respond as a nation-state, which implies some degree of compromise with reality, nor, lacking the power required, as a messianic revolutionary force, impose its will on its adversaries. When hitting something hard on its way it has slowed down or even momentarily stopped; but it has not changed course. It has not changed course because it cannot. The schizophrenia in question has also led Iran’s domestic politics into impasse. The present regime is unable to respond to Iranian society’s “normal “demands, such as the rule of law, security, economic development, welfare and cultural diversity because these are things that only a nation-state can deliver. However, in Iran today priority is given to the achievement of the revolution’s global goal of what “Supreme Guide” Ayatollah Ali Khamenei calls “The New Islamic Civilization” rather than the mundane task of dealing with bread-and-butter issues. The net result, as far as Iranian people are concerned, is that their country has had four decades of under-achievement, to say the least. Because of its demographic size, geopolitical location, natural resources, and historic pretensions, Iran has proved strong enough to suffer many Plan As without altering its trajectory. Its nuisance power has remained intact in many areas, notably in the Middle East. At the same time, it has not acquired a degree of economic, military and cultural power that includes a moderating mechanism. Is a Plan B possible? No one knows for sure. What is certain, however, is that the possibility should be discussed. This is what we propose to do in this session with a paper aimed at opening the discussion on how to nudge, help or even force Iran out of the schizophrenic trap that its current ruling elite, or history if you prefer, have set for it- a way out that points to Iran absorbing its revolutionary experience to re-become a nation-state with the needs, aspirations, hopes, fears, and patterns of behaviour of nation-states. Just as every language has its own grammar, every nation has its own rhythm and tempo when it comes to historic change and development. A fast-food approach to Iran’s multiple problems could lead to disappointment or worse. The good news is that the Islamic Revolution has failed to wipe out the culture of nationhood and statehood in Iran. Choosing its version of Islam as its sole field of reference, the current leadership has failed to develop an efficient alternative model to that of the nation-state. That makes the task of helping Iran close the chapter of reviolution and reopen a new chapter in its long history of nationhood appear that much more realistic. The goal is to revive an Iranian state for an Iranian nation. Achieving that goal requires a road-map in which all those interested in dealing with the ”Iran problem” will play a part. =========================================================================== THE FOLLOWING ISFULL TEXT OF PAPER PRESENTED BY AMIR TAHERI For almost four decades this question has haunted chancelleries around the world. During all that time, Iran has been called “the leading state sponsor of international terrorism”, part of an “axis of evil”, “the great trouble-maker” and “le perturbateur”. During those decades Iran has been involved in the longest war in history since the 30-year war in medieval Europe. It has fought a naval war with the United States, two proxy wars with Israel, a proxy war with Saudi Arabia and a war of repression in Syria alongside that country’s minority-based regime. In a series of “revolutionary operations”, that their victims regard as acts of terrorism, it has been directly or indirectly involved in the death of thousands of people, both military and civilian, in 22 countries from Argentina to Yemen and passing by Nigeria and Kuwait. In the past four decades, the Islamic Republic has seized and held hundreds of hostages from more than 40 countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Holland. In fact, not a single day has passed since November 1979 without the Islamic Republic holding some foreign hostages either in Iran itself or through proxies in Lebanon and Iraq. The international dimension of the “Iran problem” is also illustrated by Tehran’s active involvement in the wars in Syria, Iraq and Yemen not to mention its support for armed groups engaged in power struggles in Lebanon, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Bahrain and, at least until 2013, even in Turkey. In its current emanation as the Islamic Republic, Iran has also been among the world’s top three countries for the number of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience and for the number of executions. Right now over 15000 Iranians, are on death-row, having received capital punishment. The Islamic Republic has experienced the severing or suspension of diplomatic relations with more than 40 countries, perhaps an all-time record at peacetime. Whichever way you look at it there is an Iran problem. And that problem cannot be simply ignored if only because of Iran’s importance as a nation. In addition to its geostrategic location, it is one of the world’s 20 biggest countries in terms of territory, population and economic size. The emergence of more than eight million Iranians in a diaspora that covers more than 50 countries across the world gives a global flavor to the “Iran problem”. Add to that Iran’s position as heir to one of the world’s oldest and richest cultures, still present far beyond its current borders in a civilizational space called “the Persianate” , and you would appreciate why it cannot be ignored when posing a problem. But what is this problem? One is reminded of a quip attributed to Lord Palmerston when he was asked to explain the Schleswig-Holstein problem. “Only three people knew the answer,” he noted. “One was Prince Albert who is now dead. The other is a German professor who has gone mad. And the third is my humble self who has forgotten it.” One difficulty in dealing with the Iran problem is that those who faced it either refused or failed to define it before seeking a solution. That failure and/or refusal is reflected in the insipid cliché so often repeated by successive US Presidents that in dealing with Iran “all options are on the table.” Another difficulty is rooted in the fact that dealing with Iran has become an ideological dividing line in global politics. On the one side, the Islamic Republic is seen as a plucky standard-bearer of defiance against American hegemony if not actual Imperialism. Even in the US, partly thanks to President Barack Obama’s efforts to woo the Islamic Republic away from some of its undesirable attributes, Iran has become a cause celebre for the Democrats and a tar-baby for the Republicans. At the other end of the spectrum, some see Iran as the devil reincarnate that must not only be resisted but, if possible, wiped out of existence. In instances where attempts have been made to develop a pragmatic approach to the “Iran problem”, the measures tried have been discrete, dealing only with specific issues, and even then partially, thus failing to produce the desired solution. Those attempts have amounted to so many Plan As for those inside and outside Iran interested in finding a solution to the & & &” Iran Problem.” THE OVETHROW OPTION Inside Iran, many opponents of the Islamic Republic have based their Plan A on a clear demand for the overthrow of the current regime. The use of such terms as “forupashi” (disintegration), “barandazi” (overthrow), and” nabudi” (annihilation), does not hide the fact that the Plan A in question is not based on any sober clinical diagnosis and thus is deficient in conception and paralyzed in execution. Inside Iran, this time within the broader context of the current ruling establishment, we have the trend called “Islah-talaban” (reform seekers) whose adepts reject the concept of regime change and insist that what the present system needs in order to survive and faction is a series of reforms. However, despite the fact that the “reform-seekers” faction has had a leading role in the Islamic Republic, including at least two decades in control of big chunks of the executive and legislative branches, it has never been able or willing to specify what reforms it deems necessary, let alone trying to implement any. Like its rival in the “overthrow camp”, its Plan A has been more virtual than real. Needless to say the segment of the ruling establishment that controls most important levers of power has had its own Plan A which is almost exclusively aimed at self-perpetuation through sectarian propaganda, repression, social bribery and systematic violence. More recently it has tried to expand its constituency by attracting segments of its fraternal rival factions, especially former Communists and socialists, within the establishment. The chief argument used is that regime change or even changes in regime behaviour could turn Iran into “another Syria”. ENDORSEMENT OF STATUS QUO A series of popular uprisings last summer and winter is depicted as a warning that Iran could go the way of “Arab Spring” countries, a way that could lead to tragedy. Individuals who lauded “people power” and “the energy of the masses” during the revolt against the Shah now depict anti-regime marches and strikes as threats to the very existence of the country. They argue that, fraught with risks, regime change may or may not produce positive results for the nation and that a quietist approach may be the wisest course to adopt at present. Thus, their Plan A consists of an implicit endorsement of the status quo. However, after four decades it must now be clear that no meaningful reform is possible without regime change and, had such reforms been possible, there would have been no need for regime change. Outside Iran, most Plan As devised and tried by various powers interested in Iran, even if only anxious to minimize the damage it can do to their interests, have aimed at partial changes in the behavior of the Islamic Republic on specific topics. The European Union’s Plan A has aimed at persuading the Islamic Republic not to carry out terrorist operations in Europe. Between 1979 and 1995, the Islamic Republic carried out 42 operations in 11 European countries claiming scores of victims including 117 Iranian exiles assassinated by hit-squads, often consisting of Lebanese and Palestinian elements, sent by Tehran. Despite many ups and downs in relations, including a collective closure of EU embassies in Tehran at one point, the European powers, especially Britain, Germany and France have tried to bolster the EU’s Plan A through increased trade, technical cooperation and even diplomatic visits at the highest levels. Tony Blair’s Foreign Secretary Jack Straw made more visits to Tehran than to Washington. At times, his French counterpart Dominique de Villepin and their German colleague Joschka Fischer sounded like apologists for the Islamic Republic. Although one might say that the European Plan A has had some success it has not dealt with the Iran problem as a whole. And the recent resumption of terror operations backed by the Islamic Republic, as illustrated by arrests in Austria, Belgium and Denmark, show that Tehran leaders could ignore the European Plan A when and if they so desire. As far as the United States is concerned, we have witnessed several Plan As, all of them ending in failure. President Jimmy Carter’s Plan A was to embrace, not say assist, the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and to help the new Khomeinist regime establish its moorings. Carter was encouraged by the fact that, in the final months of the revolutionary insurrection against the Shah, he had established contacts with several Khomeinist leaders at the highest level and that the first Council of Ministers formed under Khomeini, with Mehdi Bazargan as Prime Minister, included five Iranians with US citizenships and/or “Green Card” permanent residency. However, just nine months after the success of the revolution, the seizure of the US Embassy in Tehran by Khomeinist militants spelled the death of Carter’s Plan A and, later, also of his presidency. Lacking a fallback position, Carter launched what was to become the key element in another Plan A that consisted of a “carrot-and-stick” approach to the “Iran problem”. Four set of sanctions formed the backbone of the new version of the American Plan A that, with certain modifications to reflect present conditions and political temperaments of the various administrations, was adopted by all of Carter’s successors with varying degrees of determination. Inside the US ruling establishment a small but influential minority, at one time vilified under the label of “neocons” promoted its own Plan A. That Plan A advocated the use of force in various forms and with various degrees of intensity from full-scale invasion, to “give-them-a-state of their own-medicine” tit-for-tats to “proximity pressure”, aiding and abetting the regime’s armed opponents including some charged with terrorism, and even a military putsch backed by the US and its allies. The use of force option has been justified with the claim that, though democracy cannot be imposed by force, force can be used to remove hurdles on the way to democratization, one example being the removal of Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq. The only time that Plan A promoted by “neocons” scored a fleeting success was in April 1988 during Ronald Reagan’s presidency, when the US navy fought a 16-hour battle with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard’s navy in the Persian Gulf with the aim of persuading Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini to stop firing on tankers under the US flag, carrying Kuwaiti oil, and to accept a UN Security Council resolution to end the Iran-Iraq war. Reagan adopted the “neocon” Plan A only after his attempts at wooing the Khomeinist rulers of Tehran by smuggling arms to them to fight Saddam Hussein's army and sending them gifts failed to change their behaviour. All of Reagan’s successors as US president adopted his Plan A with variations to emphasise either the ”stick” or the “carrot” aspect. President Barack Obama added his personal flavour by imposing the toughest sanctions on the Islamic Republic but making sure that none was actually implemented. In fact, of the 35 rounds of sanctions imposed by the US on Iran since Carter, 11 came during Obama’s presidency. US policy towards Iran has always been inspired by the “containment” strategy first developed by George Kennan in the late 1940s to counter the Soviet Union. The strategy failed to contain the USSR and may have even helped prolong the life of the Soviet Empire but gained some justification with the claim that it helped prevent a thermonuclear war. & & In the case of Iran, however, containment, highlighted under President Bill Clinton, served only to encourage the most radical factions in Tehran. Yet, in Iran’s case, fear of a real or imaginary nuclear war never existed. & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & Imposing sanctions was, in effect, nothing more than an attempt to buy time and pretend that one was “doing something.” Successive US presidents, from Carter to Obama, and possibly even to the current one Donald Trump, was never willing or able to decide what to do about “the Iran problem”. Thus, by imposing sanctions as a simulacrum of action, they resembled the man who not knowing where he wants to go parks his car somewhere but keeps the engine running. The fact that President Trump has just re-imposed the toughest sanctions imposed on Iran by his predecessors shows that the American Plan A for Iran hasn’t worked. His aides state that he may yet impose even tougher sanctions. But even if he does so, it is unlikely that the new modified Plan A would prove more effective. But what does one mean when one claims that sanctions haven’t worked? In a sense sanctions do work if only because they make life more difficult for the people of the nation subjected to them. They also work as a symbol of disapproval not to say antipathy with regard to a regime’s policies and behaviour. However, it is as far as their stated goal is concerned, which is changes of policy and/or behaviour by a regime, that sanctions often don’t work. Sanctions could lead to unintended consequences but seldom deliver the results desired. Western powers interested in Iran failed in their diagnosis of the “Iran problem” for two reasons. The first was that they focused almost exclusively on certain aspects of the Islamic Republic’s disruptive foreign policy. They did not realize that a regime’s foreign policy is a reflection, even a continuation, of its domestic policies, and that a regime that has problems with its own people is unlikely to have problem-free foreign relations. More importantly, they overlooked the schizophrenia that has afflicted Iran under the Islamic Republic. By 1981, when the Khomeinist leadership was acknowledged as the dominate force in Iranian politics, two Irans existed side by side: Iran as a state and Iran as a vehicle for a revolutionary ideology. Iran’s experience in that regard was not unique. All nations that passed through major revolutionary upheavals have suffered from similar schizophrenia with varying degrees of intensity. The first aim of all major revolutions, at least since the Great French revolution of 1789, is to destroy the state in place and create a new successor state. The Khomeinist revolution followed the same path. However, unlike the French, Russian and Chinese revolutions, to name only the best-known three, the Khomeinist revolution faced two major problems when it came to destroying the Iranian state. The first was that it lacked the philosophical, literary and historical points of reference required to develop an alternative narrative without which destroying the old to build the new is not always possible. Abundant, not to say wanton, use of the label “Islamic” could not hide the fact that the Iranian state, as forged over the past five centuries is moored in Shi’ite Islamic beliefs, traditions and values. Thus, in theory at least, the new revolutionary regime could not claim that it wished to re-Shi’ify Iran. Instead, the new regime had to borrow such Western terms as “republic” and adopt a terminology borrowed from Marxism-Leninism, albeit disguised in an Arabic lexical camouflage, could not amount to a credible alternative to the Iranian nation-state it wished to destroy. Despite purges that included the expulsion of over a quarter of a million people from the armed forces, the police, the civil service, the diplomatic apparatus, the bureaucracy, academia and the managerial elite of the public sector of the economy, the much maligned Iranian nation-state did not fade away. More importantly, partly because of the need to ward off an Iraqi invasion in 1980, the new regime was forced not only to halt its dismantling of the Iranian nation-state but, in part at least, rely on its human and institutional resources to prevent its own collapse. Unable to destroy the Iranian state, Khomeini and his entourage decided to create parallel state structures for their revolution. With help from Lebanese, Palestinian and other foreign radical groups, they created their Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a double for the national armed forces. Later, as the IRGC started to look like a regular army, they created a new double for it known as Baseej Mustadhafeen (Mobilization of the Dispossessed). As an alternative to the nation-state’s judiciary that functioned through civil and criminal courts by using a Persianised version of the Napoleonic Code, they created Islamic Revolutionary Courts with mullahs acting as judges. Alongside banks regulated by the nation-state the mullahs set up interest-free “justice and generosity” and “good credit” funds. To reduce the nation-state’s role in the economy, the new rulers confiscated thousands of private and public businesses, transferring their ownership and control to “foundations” that not only paid no taxes to but did not even publish their accounts. Despite a two-year shut-down of Iran’s universities and the purge of over 10,000 members of the faculties, the new rulers failed to Islamicise higher education. Instead they created parallel universities of their own which, by the time of this writing, have reached the staggering number of 2600. More importantly, perhaps, the new rulers gradually transformed the nation-state into a façade as far as decision-making was concerned. The Presidency, the Council of Ministers, the unicameral parliament, the various departments of the nation-state, the regular army, police and security agencies form a façade behind which policies are made and decisions are taken by a network of star-chambers converging on the “House of the Leader” (beit-e-rahbar). The presence side by side of two Irans, one reflected in a badly shaken but resilient state structure while the other reflects a wayward revolution has created a situation in which neither is able to fully function in pursuit of its interests. One may call this a Jekyll-and-Hyde situation in which the interests of Iran as a nation-state and Iran as a vehicle for revolution do not always coincide. That conflict of interests is reflected in many aspects of the regime’s domestic and foreign policies. As a nation-state Iran has no problems with any other country. In fact, it is the only country in the Middle East, and one of a few across the globe, to have no border problems with its 16 neighbours. Dating back to the pre-revolution era, Iran also has treaties of cooperation and trade with 32 countries, including the United States. Iran was the first non-European nation to be given preferential access to the then “Common Market” with an agreement signed in 1975. Iran had joint economic commissions at ministerial level with 30 nations on all five continents and visa-free travel accords with a further 40. At regional level, Iran was one of the first two Muslim countries to recognize the newly created state of Israel, albeit on a de facto basis but with a full range of political, economic and cultural relations. At the same time, Iran was a strong advocate of legitimate Palestinian rights and the initial sponsor of the first Islamic Summit held in Rabat, Morocco, to harmonize the Muslim world’s position on the Palestinian issue. In 1971 Iran became the only country to be granted full access to US weaponry, barring nuclear weapons. As a nation-state Iran enjoyed other distinctions. It was one of only three Muslim countries not to become colonized by or fall under the protection of foreign empires. But nor did it become a colonial power itself. It was also the only nation not to become involved in the global slave trade and one of the first to adopt an international covenant banning slavery. Iran did not become a participant in either of the two world wars although rival alliances violated its neutrality in both. Unlike its neighbour Turkey, during the Cold War Iran did not join either of the two rival military blocs of NATO and Warsaw Pact. It also refused to take part in the Korean War and the subsequent wars in Indochina. Wherever Iran took military action, as was the case in Oman, it was to protect its security interests as a nation-state and not in pursuit of an ideological goal. Elsewhere as in Morocco, Somalia, Sudan and Lebanon Iran’s military assistance was prompted by a concern for stability or a peacekeeping mission sanctioned by the United Nations. By the 1970s, Iran as a nation-sate had established itself as a force for peace thanks to its close ties with the Western world and cordial relations with both the Soviet Union and China. It was thanks to that distinction that the rival Cold war blocs nominated Iran’s Ambassador to the United Nations as head of the organisation’s crucial disarmament committee. Iran also hosted the monitoring stations needed in the context of the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) between the United States and the USSR. Because it always acted as a responsible and law-abiding nation-state, Iran was respected across the board. It did not try to “export” revolution and sedition, nor did it ever use terrorism as a tool of policy. The same cannot be said of the parallel “state” created by the Khomeinist rulers of Iran since the 1980s. It has been frequently condemned, often with some justification, for using terrorism sanctioned at the highest levels of the leadership as a means of furthering its aims. On occasions, the revolutionary leadership has blamed “uncontrolled elements” for acts of terror inside and outside the country. However, in almost every case acts of terror have been traced back to organs of the parallel revolutionary state in Tehran. Like other revolutions with international ambitions, the Khomeinist revolution regards Iran as primarily a base for promoting its universal message through a global revolutionary network that recognizes no frontiers. As a result, it has been both unwilling and unable to cater for Iran’s needs and aspirations as a nation. Despite its liberal use of Islamist shibboleths, it has even failed to cater for the spiritual needs of the Iranian people, hence the unprecedented growth of religious sects and organizations such as American Bible-belt-style Christianity, not to mention traditional Persian Sufism and esoteric “metaphysical” circles claiming to offer an alternative to regime-sanctioned orthodoxy. In most cases both the foreign powers interested in Iran and the domestic opponents of the new regime failed to understand the political schizophrenia caused by the Islamic Revolution. Thus their policies, let’s say their Plan As, were all based on the assumption that despite regime change in Tehran, Iran would continue to behave as a nation-state, pursuing goals and interests that any normal nation-state would espouse. At the same time, however, almost invariably they chose the parallel revolutionary organs created by the new regime, thus contributing to the further isolation and weakening of Iran’s state institutions. Worse still, some leading democracies, notably the United States, Germany and France implicitly agreed to pursue contacts and relations with the Islamic Republic outside the parametres of international law and conventional diplomatic practice. President Carter ordered his Chief of Staff Hamilton Jordan to wear false beard and flamboyant clothes to meet revolutionary figures from Tehran in Paris and in secret to discuss under-the-counter deeds. President Reagan sent two senior aides to Tehran on forged Irish passports to talk to Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini’s aides without informing the “formal’ government in Iran. President Barack Obama went even further by circumventing the United Nations’ Security Council, the United States’ Congress and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to forge his notorious “nuke deal” known as Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) through negotiations that later included Britain, China, Germany, France and Russia. French President Francois Mitterrand had an army of shady characters, many of them Levantine fixers, as intermediaries with the mullahs in Tehran. By the mid-1980s dealing with the Islamic Republic had generated a veritable industry in the West, attracting convicted felons, arms dealers, double-agents and affabulators of all shades. Some of whom were later to end up landing in American and French jails on charges unrelated to their dealings with Iran. The German government established special relations with revolutionary figures in Tehran with a mixture of business deals and political favours. At one point the German security service BND organized the hasty exfiltration of the Islamic Security Minister Ayatollah Ali Fallahian who was wanted for murder by a court in Berlin. Germany became a favourite destination for Islamic revolutionary figures seeking medical treatment, vacations and business deals. Today, despite the lack of formal diplomatic relations with Iran, Canada serves as a haven for prominent figures of the Islamic Republic and their offspring. In some cases, the powers involved decided to shut down channels of communication with the official Iranian state in favour of unofficial channels suggested by revolutionary figures. One stark example was when the Reagan administration ended contacts with the then Prime Minister Mir-Hussein Mussavi’s Cabinet in favour of a new secret channel developed by Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi and Iranian “fixer” Manuchehr Suzani and finally leading to Khomeini. In other words, Khomeini was not prepared to let the prime minister chosen by himself to pursue his goals within the parametres of a classical nation-state. Khomeini wanted the Iranian state shattered just as he had tried to disband the national army. The domestic opposition to the regime made its own mistaken diagnosis by focusing attacks on the badly shaken institutions of the Iranian state while nursing the illusion that factions within the ruling elite, first named “sazandegan “(constructors) and later “isalh-talaban” (reform-seekers) would find a way out of the impasse created by the revolution. Duality established Despite all that, by the late 1980s the new revolutionary ruling elite had realised that it could not totally destroy the Iranian state whose administrative network, historic memory and technical know-how kept the country afloat even at the worst of times. By the early 1990s that duality had been established as a key feature of Iranian life under the Islamic Republic. Both the foreign powers and the domestic opposition were demanding from a revolution what only a state can deliver. Paradoxically, the use of that method further weakened the very state that alone might have been able to satisfy at least part of the demands in a quest for common interest. Regardless of how it is defined, the “Iran problem” cannot be solved without the restoration of a culture of statehood (culture etatique) which, in turn, requires the downgrading of the revolution into part of a much larger historic, political and existential reality. In other words, Iran must cease to be a vehicle for revolution and re-become a nation-state that is both willing and able to develop a national rather than a revolutionary strategy. And that is the central component of what we propose as a Plan B for Iran. There is no doubt that Iran will, in time, absorb its revolutionary experience and re-emerge as a nation-state. A revolution is like an attack of fever and no organism can forever live in a feverish state. Without recalling much older times, the Russian and Chinese revolutions of the 20th century ended up fading into the background, albeit in different ways, thus allowing the re-emergence of nation-state structures in both countries. That does not mean that the current regimes in either China or Russia are paragons of good governance let alone democracy. What is important, however, is that neither Russia nor China today behave as revolutionary agents provoking disruption, violence and war. Seen from the West they cannot be considered as friends, let alone allies. But nor could they be regarded as enemies and/or foes. In their new manifestation as nation-states, they are adversaries and rivals that could, given time and further evolution, even become partners and friends. Paradoxically, because the Khomeinist revolution did not succeed in totally destroying state structures in Iran, something that both the Bolsheviks in Russia and the Maoists in China did in their respective countries, chaperoning the return of Iran as a nation-state may prove a less challenging task. What is to be done? A number of ideas inspired by the need to lead Iran away from its revolutionary turmoil and back into its historic course as one of the world’s oldest and best established nation-states have been developed and intermittently discussed even within the Khomeinist ruling elite. One idea concerns the unification of Iran’s military forces, now numbering six more or less autonomous entities. Iran’s national army is still intact, albeit on a smaller scale and within constraints imposed by the revolution. Thanks to its historic memory, the prestige it still enjoys in public opinion, its military culture and organizational methods it had managed to retain its specific personality by meeting numerous challenges under the revolutionary regime. The idea of merging the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), an organization that, for reasons beyond our scope here, has failed to develop an esprit de corps, with the traditional armed forces to create a new and expanded national army was officially discussed in the mid-1990s. Another idea is the merger of the various Islamic revolutionary courts with the traditional long-established Ministry of Justice courts, enabling the Iranian nation-state to regain control of the judiciary. The legal framework for such a move already exists as the Islamic Revolutionary Courts were initially set up for a period of five years, long expired. More importantly, perhaps, fewer and fewer people now take their cases to such semi-official courts which are being used or rather abused to hamper the legal system. Iran as a revolution is also present through dozens of so-called foundations, façade companies, and unchartered charities initially based on public sector corporations or businesses confiscated from private owners. They are part of a parallel black economy that operates outside the laws and regulations of the nation-state. Through at least 30 companies, black economy is even extended to the all-important oil sector which is nominally under state control. Bringing those companies under the control of the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) would be a major step towards restoring the Iranian nation-state. Another idea is to restore the authority of the state on the educational sector which directly concerns some 30 million Iranians of school-going age. Over the past decades, revolutionary mullahs and their partners have confiscated numerous state schools and transformed them into private profit-making entreprises. The restoration of national curricula at all levels of education and the re-introduction of free education at least up to secondary school would also help speed up the re-emergence of the state as the principal framework for Iranian national existence. Ultimately, however, the full restoration of the Iranian state would not be possible without the abolition of organs such as the office of the” Supreme Guide”, the Custodians’ Council and the Assembly of Experts. A platform based on the restoration of the state with the slogan “Iranian state for Iranian nation” could give the opposition a clear objective against which its performance could be checked. Such a shared goal could also unite the many opponents and critics of the regime including a segment of the current ruling elite within both the military establishment and the civil service. Opposition energies that are now partly spent on ideological polemics, self-indulgent nay-saying and even Utopian fantasies could be devoted to the promotion of a concrete project aimed at regime change through the reconstruction of the Iranian nation-state. As far as foreign powers interested in Iran are concerned clinical analysis of the Iranian situation would reveal an impasse in which no decision-maker in Tehran could devise let alone implement the policies needed to normalise relations with the outside world. A revolution cannot abide by the rules set for a world of nation-states. This is why that even with the best goodwill, Tehran’s leaders are unable to resolve even the most minute foreign relations policy through diplomacy. The assumption that the Islamic Republic’s strategy is based on a desire to defend and promote Islam is wide of the mark not to say fanciful. A few examples would illustrate that. In the dispute over the Nagorno-Karabkh enclave, the Islamic Republic has always sided with Christian Armenia against Azerbaijan where Shi’ite Muslims of Iranian origin form a majority. Using virulent anti-Israeli rhetoric, Khomeinist leaders make much of their claimed attachment to Palestine as an example of Muslims suffering under non-Muslim occupation. However, they have nothing to say about the repression of Muslims by Russia in such places as Chechnya and Dagestan or by China in East Turkestan (Xinjiang). Last October they denied a delegation of Uighurs visas to visit Iran and turned down a request by them to open an office in Tehran. Nor has the Islamic Republic shown much concern about the expulsion by Burma (Myanmar) of more than a million Rohyngia Muslims. During the Yugoslav crisis, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, then President of the Islamic Republic, paid a state visit to Belgrade to forge an alliance with the Serbs in the name of “non-aligned” unity. As a direct result the Islamic Republic supplied arms to the Serbs, mostly Orthodox Christians, to massacre Bosnian and Albanian Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo. Even today, the Islamic Republic refuses to recognise Muslim Kosovo as a state but endorses the Russian annexation of South Ossetia which also has a Muslim majority. The Islamic Republic regards the Palestinian Authority led by Mahmoud Abbas as an enemy while also keeping relations with Hamas within strict limits. Its favourite Palestinian proxy is the Islamic Front for the liberation of Jihad which is totally subservient to Tehran. The Islamic Republic’s closest and most consistent allies in the past four decades have been Cuba, Venezuela, North Korea, Zimbabwe and Syria, none of them under Muslim rule. In confronting the Islamic Republic in Tehran, foreign powers should realise that they are in conflict with neither Iran as a nation nor Islam as a religion. The adoption of anti-Iranian and/or anti-Islamic rhetoric by foreign powers, as has been the case with some governments both in the West and the Middle East, is at best a diversion and at worst could legitimise the regime’s claim of defending the nation and its faith. In practice, however, most Western powers and their regional allies have tried to downgrade contacts with the nation-state element of Iran’s complex reality in favour of the revolutionary element. One example: when, in the wake of a raid by radical Khomeinists on the British Embassy in Tehran, Great Britain severed diplomatic ties with Iran it ordered the closure of the official Iranian Embassy in London but allowed the unofficial embassy of the “Supreme Guide” Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to continue operations without hindrance. The fact that the unofficial embassy is larger in terms of personnel, richer in terms of resources and more active in terms of questionable activities than the official embassy was ignored. Even after it was reopened the official embassy was not allowed to have even a bank account through which to pay it employees while the unofficial embassy used full banking facilities for operations including the funding of radical Islamist groups in the United Kingdom. London isn’t the only capital where the revolutionary element of the Islamic Republic maintains unofficial embassies along the formal embassies of Iran as a nation-state. Such unofficial embassies operate in no fewer than 40 capitals, including almost all major European capitals plus at least 10 Arab capitals, notably Oman, Qatar, the UAE and Kuwait. The closure of those unofficial embassies or at least demanding that they be absorbed into the official embassies may contribute to nudging Iran back into behaving like a normal nation-state. Most foreign powers seemed to have simply set aside the entire panoply of treaties, agreements and traditional forms of cooperation established with the Iranian state before the revolution. Reviving at least some of those could help solve some of the problems that Iran has with the outside world while helping the cause of reviving the culture of statehood in Tehran. One example: Iran has a full treaty with Afghanistan to operate and guarantee a system of water-sharing in the four zones of Haririrud, Parianrud, Farahrud and Hirmand rivers. That system was tested over years to the benefit of the two neighbours. However, the revolutionary element in Tehran tried to by-pass it by claiming that, as a relic of Iran under the Shah, it did not serve the interests of the regime’s messianic mission. Sadly, the Afghan government agreed to by-pass the treaty and enter a game the rules of which were set by the most radical faction within the regime. At least 20 countries, ranging from Israel and Great Britain to Zimbabwe owe Iran billions of dollars in the form of loans obtained or oil imported from Iran before the revolution. However, despite occasional noises made in Tehran about the subject no progress towards repayment has been made because the Islamic Revolution, in its revolutionary persona, is unwilling and unable to attempt what a normal nation-state does in ordering relations with the outside world. Four decades of underachievement As it prepares to mark its 40th anniversary, the Khomeinist revolution may be rated as an example of gross underachievement if not total failure. By the time it was 40, the Bolshevik Revolution had transformed Russia, a ramshackle 19th century empire, into a 20th century superpower capable of sending the first man into the space. It had also succeeded in spreading its ideology throughout the world and helped the emergence of a bloc of Communist states more or less resigned to, if not devoted to its leadership. The fact that the USSR, its obvious flaws notwithstanding, managed to live on for four more decades was, at least in part, due to its self-transformation into a nation-state via the “Socialism in one-country” doctrine that replaced the “permanent revolution” slogan. Similarly, on its 40th birthday the Chinese Revolution had reverted to a culture of statehood, traced a path back into normality, created a network of neighbours sharing its ideology and laid the foundations for reforms and developments destined to make it a global economic power-house. The same cannot be said of the Khomeinist Revolution. No other nation has adopted its model while it stands almost alone, bereft of friends let alone credible allies. Forty years later, Iran is poorer than it was before the revolution and, as a recent report by Iranian academics clearly shows, underperforming in almost all fields of human development. The Khomeinist system today resembles a crumbling edifice, an anachronism that must be bequeathed to history. Iran must absorb that experience and re-emerge as a nation-state claiming the place it deserves in the community of nations. The revived Iranian nation-state may not conform to the ideal, not to say Utopian, models envisaged and dreamt of by many Iranians and some of the powers interested in Iran. But it will have the merit of shedding the illusions that have claimed so many lives, shattered many more lives and led our nation into an impasse. As one of the world’s oldest nation-states Iran could close the Khommeinist parenthesis with a minimum of damage to itself and to others. In doing so, Iran would need the dedication of all its children, the support of all its friends, and the goodwill of all those who uphold the universal values of freedom and human dignity. END Copyright Amir Taheri 2018 |

&

التعليقات